Historian Tippin shares mountains of research into Pearl Bryan tragedy

As Putnam County historian turned detective and super researcher, Larry Tippin has immersed himself into “The Life and Times of Pearl Bryan,” a two-part presentation about the 1896 “Crime of the Century” that concludes this Thursday, June 29 at the Putnam County Museum.

During his first two-hour presentation, Tippin told nearly 100 onlookers that the Jan. 31/Feb. 1, 1896 murder of Pearl Bryan, a 23-year-old Greencastle girl, “is a very complex story that’s never really been told.”

In fact, Tippin was amazed that during a presentation last fall on burial practices, “the interesting case of Pearl Bryan” was not even included.

“It’s like, ‘We’re not going to talk about it,’” Tippin said of an infamous case in which Pearl Bryan was murdered and her headless body discarded in a field near Fort Thomas, Ky., with two men being hanged as a result in what would be the last public hangings in Campbell County, Ky.

Although much was written about Pearl Bryan at the time, Tippin said he had two goals in mind when he doggedly dug into the case, tracking the story through 3,200 pages of Kentucky trial records, some so old and fragile they couldn’t be separated from one another lest they crumbled into dust.

But Tippin, whose own family goes back to the 1830s in Putnam County, persisted through 4,000 pages in source documents and several visits to the scene of the crime in Kentucky, just across the Ohio River from Cincinnati.

Tippin vowed to present a fact-based study of the Pearl Bryan tragedy with “actual, factual information,” and said he wanted to “make as many people as possible aware of the ‘Crime of the Century.’”

“I mean (it was in) every newspaper in the country. This was a significant story for them,” Tippin stressed.

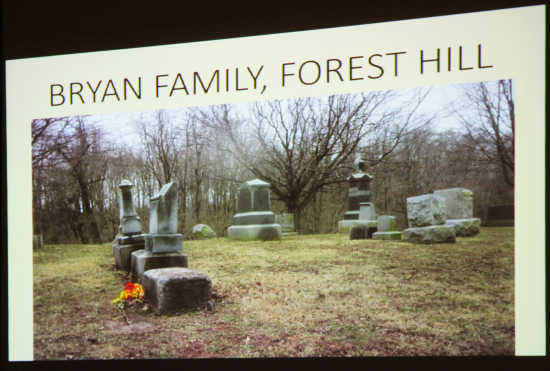

With Pearl buried in Forest Hill Cemetery, the story was so sensational that passing trains would often stop and let passengers get off to chip a piece from Pearl’s headstone or leave pennies heads-up on the monument. That went on so long, the headstone itself was ultimately buried at Forest Hill.

Meanwhile, tourists so routinely visited the scene of the crime in Kentucky that local residents would set up shop and sell sandwiches and lemonade there.

Yet Tippin explained that when he began his research locally, if you tried to find out about Pearl Bryan, information was pretty minimal. You could see where she lived in the two-story home (now used by Res-Care) along the east side of U.S. 231, just north of Primrose Lane and the entrance to Greencastle Christian Church. You can find her gravesite at Forest Hill Cemetery, “or what’s left of it,” or you could visit the library and thumb through a few files and see a couple old photos.

“That’s not enough,” Tippin said, the historian in him rising to the surface as he vowed to research the family, the woman and the crime much deeper and “found an enormous amount of information on Pearl.”

That’s essentially why Tippin’s presentation is occurring over two consecutive Thursdays.

“I’ve been waiting to do this for about six months,” he said, explaining he has analyzed hundreds of newspaper articles, indexed and transcribed representative stories, located actual trial transcripts in the Campbell County clerk’s office and made more than 3,000 digital images of those transcripts and depositions.

But because of multiple errors in source documents, Tippin was forced to dive even deeper into his research, examining the lives of family members, the late-Victorian Era climate in Greencastle in 1896 and the background of the men hanged for Pearl’s murder.

Some of the simple facts about Pearl and the Bryan family have been wrong in publications for years, Tippin said.

For example, she is almost always referred to as the youngest of 12 children and listed as 22 years old. In reality, she was the second youngest Bryan child and was 23 at the time of her death.

Even court records continually mixed up facts like the name of Forest Hill Cemetery, often calling it “Forest Lawn” by mistake, while trial transcripts mixed up Greencastle and Greenfield, noting that the Bryan family lived in Hancock County, near Greencastle. Greenfield, of course, is in Hancock County. And many times the last name Bryan was typed or written as “Bryant.”

Mistakes like those, Tippin suggested, have made the research difficult and often impugned the validity of what’s been written about the victim and the case over the past 120 years.

“Two Cincinnati detectives who thought they were the greatest thing since sliced bread wrote a book about it but made significant errors,” Tippin noted.

However, what has been accurately portrayed over the years is that Pearl found out, presumably during November 1895, that she was pregnant out of wedlock with a child fathered by Scott Jackson, who resided with his mother at 632 E. Washington St. in Greencastle after his half-sister Minnie married Edwin Post, a professor of Classics at DePauw. Next-door neighbor William Wood, Bryan’s second cousin, reportedly introduced Jackson to Pearl and the two engaged in an intimate relationship that left her pregnant.

At the time, Jackson was working for local dentist Dr. Gillespie in a big white house across the railroad tracks on West Walnut Street. Jackson reportedly told the dentist that he and Pearl had been intimate three or four times, including in the dental office itself. He also reportedly vowed he “would never marry her.”

In late summer 1895, Jackson enrolls in a Cincinnati dental school and abruptly ends his relationship with Pearl.

“I really wondered what Pearl’s thought process was,” Tippin said, indicating however that he refused to cave in to pure conjecture in the case. “We’re not going to do that,” he continued. “We’re not going to make things up.”

The plot thickens on Jan. 27, 1895 when Pearl tells her family she is taking the train to Indianapolis to visit an old high school friend (Pearl graduated from Greencastle High School in 1892).

However, she is instead headed to Cincinnati where Jackson and his roommate, Alonzo Walling, the other man later hanged for the murder, were to meet her but missed her at the station. The following day, she sends word to the dental college that she has arrived and they spend the next couple of days in Cincinnati.

That’s where witnesses overheard a significant argument outside a music store on Jan. 31, Tippin said.

At the end of the argument, she is reportedly overheard to say, “Mr. Jackson, you’re not doing what you said you would do and I’m going back to Greencastle tonight.”

She never returns, of course, as Jackson supposedly doctors her drink with cocaine and she passes out. Walling then rents a horse and carriage and arranges for George Jackson (no relation to Scott) to drive the two men and their “patient” to Kentucky.

Around midnight, they cross the bridge into Kentucky and the driver attempts to hop off, only to have Walling pull a gun on him and convince him to continue to the Fort Thomas, Ky., area, about five miles from Cincinnati.

There the driver stops the carriage and the three passengers get out, climb a three-board fence and disappear into the night until driver Jackson hears what he calls “a peculiar noise.” That spooks him into tying up the horse, jumping off and running back to Ohio.

That’s the point at which Tippin stopped his story Thursday. He will pick up the details this week at 6:30 p.m. Thursday at the Putnam County Museum.

Of course, the story continues with Pearl’s headless body being discovered by a Kentucky teenager and her identity being revealed four days later through her distinctive webbed feet and tiny shoes -- size 3 from Louis and Hays, a Greencastle shoe store.

Thursday night two members of the Bryan family -- great-great-great-granddaughters of Pearl’s brother James Bryan -- attended the Tippin program after meeting with him earlier about his research. Kathy Bryan Gross lives at Heritage Lake, while Kristie Bryan Spear (accompanied by husband Brian Spear) resides at Roachdale.

Tippin shared that the family had a female relative who would get up and leave the room if anyone ever mentioned Pearl.

“We weren’t allowed to say her name,” Kathy said of Pearl Bryan.